A Story of Survival, Memory,

and Returns

A Story of Survival, Memory,

and Returns

An online Exhibition by the Galicia Jewish Museum, Kraków, Poland

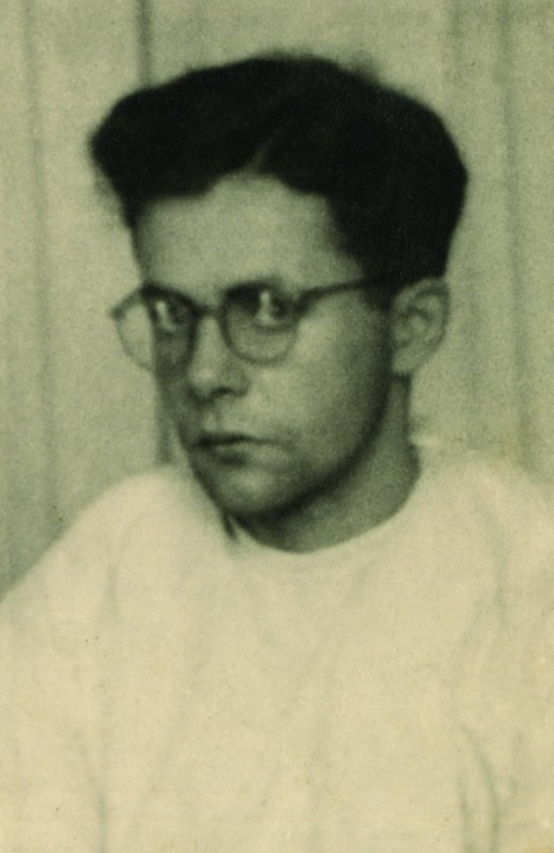

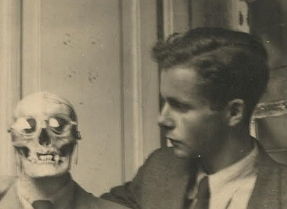

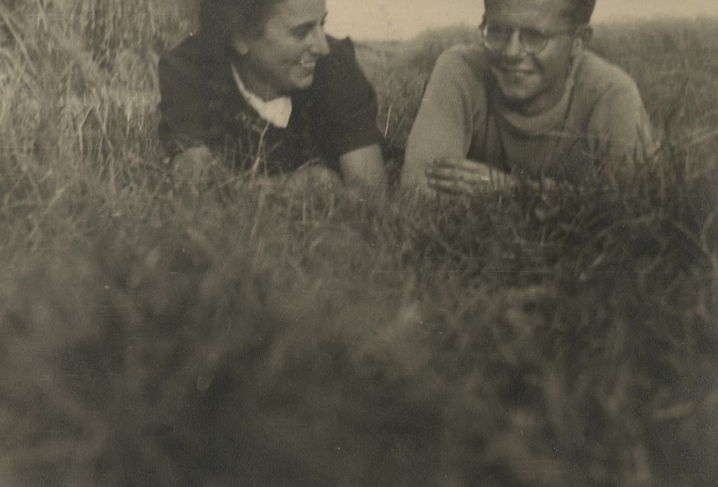

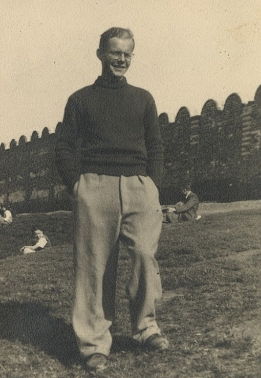

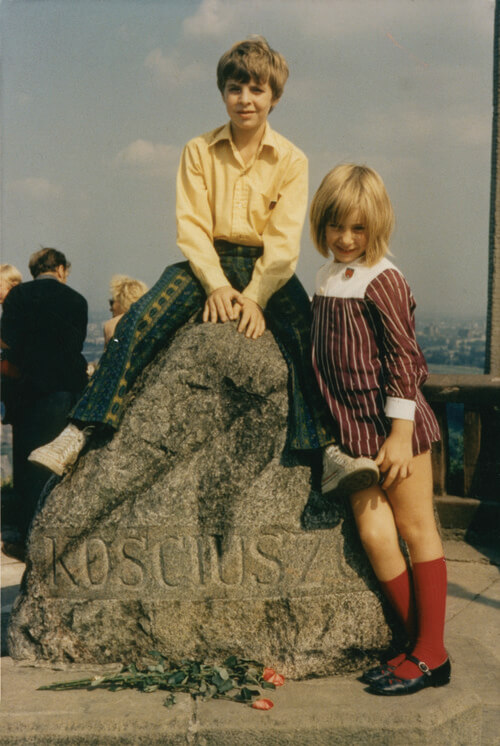

Richard Ores was born to a Jewish family in the center of Kraków. He was fifteen years old when the war broke out. He survived and spent most of the rest of his life in the United States. Even though he lived there for more than fifty years, he continued to feel deeply connected to Poland. He made dozens of trips back to his hometown, often bringing his family with him.

This exhibition tells the story of Richard, his family, and their relationship to Poland over nearly a century. Richard was fascinated with photography and filmmaking his entire life, endlessly documenting his experiences and the people around him. In creating this exhibition, we relied on many of the photos and videos Richard created, as well as interviews with members of his family.

On the eve of World War II, Jews made up nearly 25 percent of Kraków’s population—56,000 people in a city of about 250,000. They lived mostly in the neighborhoods of Kazimierz (the historical Jewish quarter), Stradom, and Podgórze. Some well-off, assimilated families moved to the newer and more prestigious parts of the city.

In Kraków in the 1930s, there were several Jewish cultural organizations, political parties, social clubs, and dozens of newspapers. Jewish religious life thrived in the old synagogues of Kazimierz, the progressive Tempel synagogue, and smaller prayer houses scattered throughout the city. There was also a significant population of secular Jews.

Krakow's Jews were an integral part of the city's community and actively participated in its life. Many of them had a significant impact on the cultural, social, and economic face of the city.

The Second World War broke out on September 1, 1939, with the German invasion of Poland. In a rapid campaign, the German forces, more numerous and much better equipped than the Polish Army, quickly captured one city after another.

The first bombs fell on Kraków in the early morning of September 1, 1939. Five days later, on September 6, 1939, German troops occupied the city.

Almost immediately after the invasion of Poland, the Germans started introducing anti-Jewish laws. In September 1939, they required all Jewish residents to register with the authorities, and one month later they introduced separate identity cards for Jews and conscripted Jews for forced labor. Starting on December 1, 1939, every Jewish resident was required to wear a white armband with a blue Star of David on their right arm. From the beginning of 1940, Jews were not allowed to move out of their homes and had to abide by a curfew between 9 p.m. and 5 a.m.

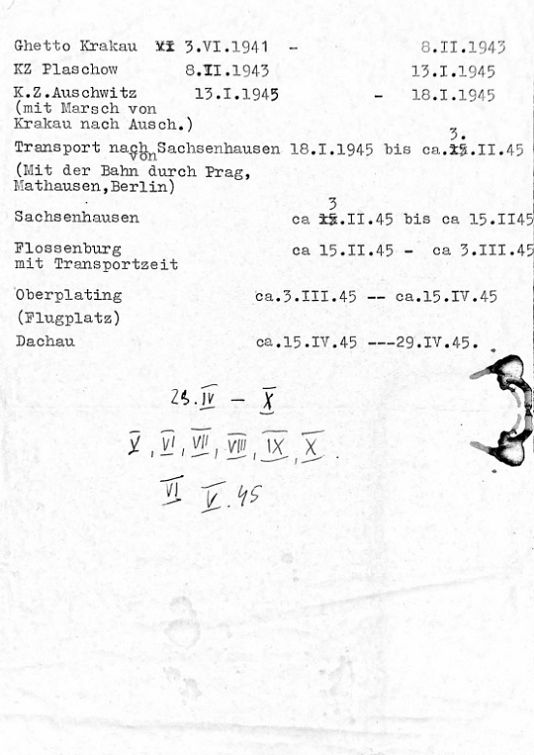

In March 1941, the German occupation authorities decided to create a ghetto in Kraków, where Jews who received a permit to stay in the city were made to reside. The rest had to leave Kraków. About 15,000 Jews were forced into the ghetto between March 3 and 20, 1941. From October 1941, leaving the ghetto without permission was punishable by death.

Photographs

from

the jar

Between 1946 and 1954, about 140,000 Holocaust survivors emigrated to the United States, nearly half of them settling in New York City. In the immediate postwar years, they sought both to commemorate their lost families and communities and to embrace the postwar American optimism around them. While survivors held and attended small ceremonies and gatherings, most Jews in America were not talking publicly about the Holocaust (a term for the genocide that wasn’t in wide use until the 1960s).

Having survived concentration camps, the gulag, forced labor, and years of hiding, they arrived in an America that was experiencing a period of incredible growth—the baby boom and the Golden Age of American capitalism. The contrast between what they had endured and where they now found themselves could not have been greater.

Only 10 percent of Polish Jews survived World War II. The vast majority of the survivors left Poland in successive waves of emigration, from 1945 through the 1970s. Likely fewer than 30,000 Jews remained, concentrated around the largest cities.

The attitude of survivors abroad toward Poland was often complicated. On the one hand, they cultivated an idealized memory of prewar life. On the other, many considered their country of origin to be a cemetery, full of ruins and hostile people. These two images of Poland were difficult to reconcile.

Many survivors completely cut themselves off from their Polish heritage. Their children were to be Americans, Israelis, Swedes, or French, with no ties to their parents’ homeland. Many refused to visit Poland for decades, or even forever. There were, however, some exceptions.

For his entire life, Richard Ores maintained relationships with a range of Polish artists and intellectuals. He often hosted them in his home in the United States, and also exchanged letters with many of them.

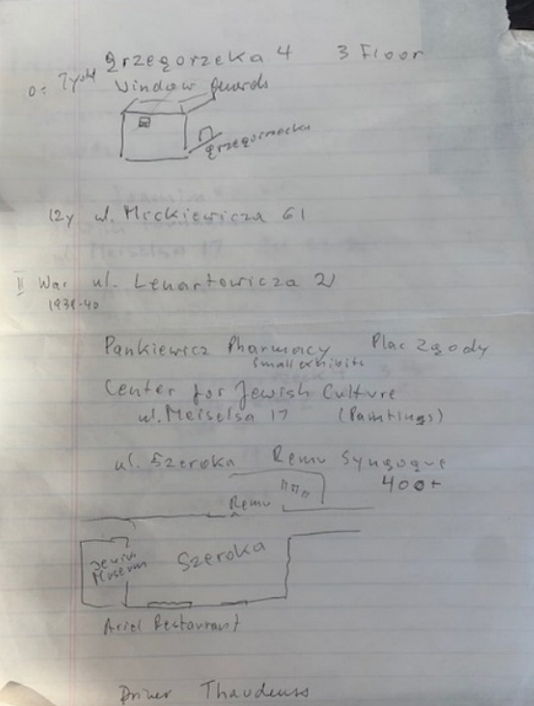

He kept up with a group of friends in Kraków, and regularly met them during his visits. These included Tadeusz Pankiewicz, a Polish pharmacist who owned the Eagle Pharmacy, which operated in the Kraków Ghetto, and Dr. Julian Aleksandrowicz, a hematologist who ran the hospital for the chronically ill in the ghetto and later became a physician in the Polish resistance. Dr. Aleksandrowicz also helped save Richard’s life in the ghetto. For many years after the war, he was the head of the Hematology Clinic at Jagiellonian University Medical College in Kraków. Richard was directly involved in the development and growth of this clinic, mostly by fundraising and supplying it with medical equipment from the US.

Until the end of his life, Richard was friends with Dr. Aleksander Skotnicki, who took over the hematology clinic after the death of Dr. Aleksandrowicz. In 1992, Dr. Skotnicki organized a photographic exhibition about life in occupied Kraków, which included some of the photos in Richard’s collection. In 2012, a year after Richard died, Dr. Skotnicki published a book about him.

Photographs from Richard's

collection showing places

connected to his life in prewar

Kraków.

Zakopane

Warsaw

Auschwitz-Birkenau

Bełżec was one of three death camps created to fulfil Operation Reinhardt - the planned murder of Polish Jews in the General Government. Odilo Globočnik, the SS and Police Leader in Lublin, was put in charge of organizing these systematic killings, and established Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka to carry out this extermination programme. Bełżec was the first of these death camps to be constructed and was located in south-eastern Poland along the Lublin-Lviv railway line. The first deportees to Bełżec arrived on train on 17 March 1942, from the ghettos in Lublin and Lviv. Polish Jews were immediately killed on arrival in stationary gas chambers. Deportations began from Krakow from June 1942.

In total, around 450,000 Jews were deported to the camp from around 440 different towns. Only two are known to have survived, including Rudolf Reder, who is the only survivor to give testimony of his time at Bełżec. As part of the Sonderkommando, Reder was forced to assist in the disposal of corpses from the gas chambers. He described his experiences in Bełżec, a book which was first published in 1946. In December 1942, the Germans began the liquidation of Bełżec. In an attempt to erase all traces of genocide, mass graves were exhumed and the bodies of murdered Jews were burned. Today, a memorial, built in 2004, stands at Bełżec to commemorate all who were killed at this camp.

Bełżec

In 1993, Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List arrived in cinemas and immediately became an important reference point for Holocaust survivors and their families. The film’s popularity demonstrated a great public interest in the history of the Holocaust, and many survivors point to the film as one of the catalysts that led them to speak more openly about their experiences during the war.